- Canadian & World History

- Posts

- The Men Who Made British Columbia

The Men Who Made British Columbia

View of Victoria from James Bay in 1862. The city was incorporated that year as a result of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush. (Public Domain)

British Columbians and Vancouver Islanders in the Confederation era, like Maritimers and Newfoundlanders, had three choices: become part of the United States, go it alone in splendid isolation, or join a ragged expansionist sub-empire calling itself Canada. Americans took for granted that B.C. would join the United States. A common refrain was: “When British Columbia belongs to us…” Another was: “when we get Vancouver’s Island…” Both were overheard in 1868 by Sir Henry Pering Pellew Crease, the highly educated Englishman who served as Attorney-General of B.C., according to “The West Beyond the West: A History of British Columbia” by Jean Barman.

For Vancouver Islanders, the least palatable option was to join Ottawa. Most had not come from Canada but directly from Britain, India, or other imperial parts. “With Canada, we had nothing to do,” the locals would say. “Our trade was with the U.S. or England.” There was no rail link with Montreal. (That came, thanks to John A. Macdonald and Sir William Van Horne, in 1885.) A canal across the Isthmus of Panama would reduce the distance by sea to Halifax (or England) by half, making B.C. less isolated—but the canal was not built (by the Americans) until 1914.

Waging the fight against annexation were two camps that rivalled each other: on the one hand, the Confederation League, men especially from mainland B.C. who saw Union with Canada, together with responsible government, as the summum bonum (the highest good). They included John Robson, editor of the New Westminster British Columbian, who served as premier from 1889–92. His brother, the Rev. Ebenezer Robson, was a Methodist missionary who evangelized the mining camps from his canoe, called the Wesleyan.

Sir James Douglas, Governor of British Columbia, circa 1865. (Public Domain)

On the other hand stood the highly educated Island squirearchy around Gov. James Douglas and his successors, Frederick Seymour and Sir Arthur Kennedy, enjoying their miniature Raj based at the old HBC Fort Victoria, with rambling English gardens, afternoon tea, garden parties, languorous afternoons cricketing, and horse-racing on the grassland around Beacon Hill—the older generation with their HBC, Indian Army, and Royal Navy pensions. Mining, fishing, and forestry—the foundations of prosperity and growth on which civilized life depended completely, as they do today—were up and running by 1850.

At the height of the West Coast cold war, the Royal Navy Pacific Station at Esquimalt was commanded by Rear Admiral Robert Lambert Baynes. His flagship from 1857 to 1861 was the 84-gun HMS Ganges, launched in 1821 at Bombay Dockyard. H.M. ships projected hard power, while onshore garrison-style balls with naval officers in frock coats and cocked hats and carrying swords conveyed tradition, self-confidence, and soft power. Intrepid Capt. George Henry Richards had done the first detailed charts, surveying the whole coast aboard HMS Plumper and HMS Hecate, continuing the great work started by Capt. George Vancouver. They were playing for keeps!

The islanders stared down the American threat at least five times. Their first coup, in 1850, was to formalize the Colony of Vancouver Island with Victoria as its capital. Secondly, when gold was discovered on the Queen Charlottes and U.S. penetration loomed, the remote islands were declared a junior colony in 1852, and “Lieutenant-Governor of the Queen Charlotte Islands” was added to Douglas’s title. Thirdly, when the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush drew in thousands of Yankee fortune-seekers, the B.C. mainland, then called New Caledonia, was erected in 1858 as a Crown colony. With a new name, British Columbia, chosen by Queen Victoria, the capital remained Fort Langley, originally built by HBC in 1827. (“Caledonia” was what the Romans called the forested western Scottish Highlands in the time of the caesars.)

Fourthly, plucky Vancouver Island nearly came to blows with the United States during the 1859 “Pig War” over the boundary with the San Juan Islands. Captain Geoffrey Hornby (who later commanded the entire Royal Navy as Admiral of the Fleet) with a flotilla of five ships and a company of Royal Marines, kept the Americans at bay.

Sir Geoffrey Hornby, Admiral of the Fleet, in 1895. (Public Domain)

Fifthly, American gold-seekers spreading north of Barkerville again obliged the British in 1862 to create the Stickeen (Stikine) Territory, which was merged with B.C. a year later. When the United States bought Alaska from Russia for about two cents an acre in 1867, it looked as if the entire West Coast might inevitably be absorbed into the burgeoning Republic. That, too, was prevented.

Great Britain’s strategy for North American security was to maintain strong armed forces, establish the Dominion of Canada (1864–67), and then gradually withdraw British forces to appease the United States. In 1866, the British united B.C. as a single colony. The capital was moved to Victoria in 1868. Finally, in 1871, B.C. joined Confederation. In time, the Royal Navy withdrew from Esquimalt in 1905.

A leading voice, and the ringleader of the Confederation League, was a Halifax Loyalist greengrocer turned gold prospector named William Alexander Smith. Rather than call himself Bill Smith, he adopted the crazy nom de guerre Amor de Cosmos because, he said, he loved “order, beauty, the world, the universe.”

Arriving in Victoria in 1858, he launched a newspaper, the British Colonist, to promote federation. He compared the governor’s circle to the old Family Compact and called for responsible government. He carried a “big-handled stick hung on the forearm, and not used for locomotion.” He served in the Island Assembly from 1863–66 and then sat in B.C.’s upper house, the Legislative Council, in 1867–68 and 1870–71.

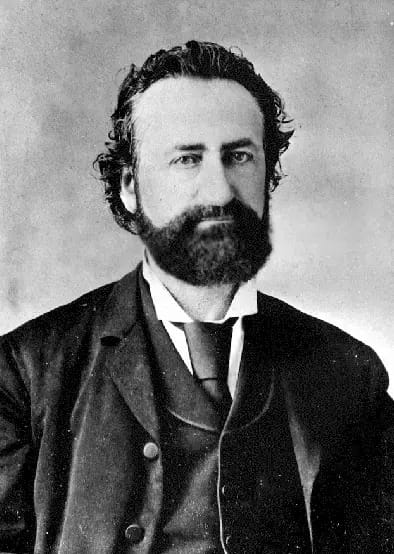

Amor de Cosmos, circa the 1870s. (Public Domain)

De Cosmos attacked the governor’s circle of cronies and “his own family members and friends,” but that was not quite fair. The founders of B.C. were a league of extraordinary gentlemen. Sir Henry Crease was typical. Born in a manor house in Cornwall and educated at Cambridge, he sailed for Victoria in 1858 and worked for the brilliant B.C. Supreme Court Judge Matthew Baillie Begbie (Cambridge and Lincoln’s Inn), who had come 10 years earlier to bestow the best of British law. That summer, 25,000 American gold diggers passed through Victoria and the province was boiling up into an incipient Wild West. Begbie, like Douglas, was the right man at the right time. Contrary to myth, he learned native languages and was more likely to pardon natives than white men.

Douglas had asked Britain to provide “gentlemen of the best education and ability.” His predecessor, Richard Blanshard, had been decorated for bravery during the Sikh War of 1848–49, arriving in 1849. Robert Burnaby, active in business and politics, arrived in 1858 from Her Majesty’s Customs Office, with a recommendation from Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Baron Lytton (1803–1873) was a man of letters and a politician; he coined phrases like “the pen is mightier than the sword,” “the pursuit of the almighty dollar,” “the great unwashed,” and “It was a dark and stormy night.” He also sent many talented men to the colony.

Lytton’s greatest protégé was Colonel Richard Clement Moody, commanding 150 Royal Engineers of “superior discipline and intelligence” to build the Cariboo Road. They established a new capital, Queensborough (later New Westminster), which Moody called “the right place in all respects,” the nucleus for “a second England on the shores of the Pacific.”

Not all Lytton’s picks were a success. George Hunter Cary quit his post in 1863 to join the gold rush. He became a brawler, arrested for “riding furiously” through town and across the shaky James Bay bridge. (He chose jail rather than pay bail.) Later, he attacked an enemy in the street with a horsewhip and in return got a “much damaged” face.

Joseph Trutch, first Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia, in June 1870. (Public Domain)

One night, Cary was seen in the garden planting “peas among potatoes at midnight with a candle.” A doctor ruled him insane. His friends convinced him to return to England by presenting him with a forged “telegram announcing that he was to be appointed Lord Chancellor at a salary of £15,000 per annum.” Cary took the bait, and his family cared for him at home until he died a year later.

More typical was John Sebastian Helmcken, born in England of German background. He arrived in 1850 as the HBC surgeon and was elected the first speaker of the Assembly in 1856. He married Douglas’s daughter (which did not help with the “family compact” image). He was “the only man living who could sit down and write the whole history of British Columbia from personal knowledge,” wrote Dorothy Blakey-Smith in “The Reminiscences of Doctor John Sebastian Helmcken.”

On Sept. 14, 1868, Amor de Cosmos marshalled 26 delegates of the Confederation League to meet at the Yale Convention, at a waning gold rush hub set among magnificent mountains 150 kilometres up the Fraser River from Fort Langley. Needless to say, they recommended union with Canada. It was fitting that de Cosmos served as the second premier (1872–74).

Another key figure in B.C. Confederation was an English engineer named Joseph Trutch, who arrived in 1858. He built some of the most difficult sections of the Cariboo Road, surveyed Gastown (part of Vancouver), and built B.C.’s first suspension bridge at Spuzzum. He was selected as one of three delegates to negotiate the terms in Ottawa. Cartier and Macdonald then chose Trutch as the first Lieutenant Governor of B.C., and he ensured that rather than rule like an autocrat, from then on the governor would support the democratically elected administration.

It is therefore a sad irony that, in the name of reconciliation, Trutch’s name was erased in 2022 from a Victoria street and replaced with səʔit, and in 2025 from a Vancouver street, now šxʷməθkʷəy̓əmasəm. Canada’s self-administered historical lobotomy continues.